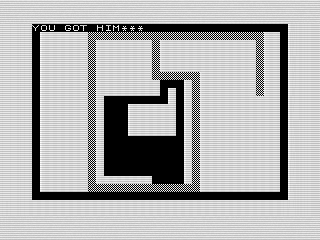

Trail Blazer is my ZX81 Tribute to Tron’s Light Cycles

Run the enemy into your trail using the ZX81’s arrow keys. But, be careful not to crash yourself.

One of the coolest movies when I was a young teenager was Disney’s Tron. What geeky kid didn’t want to watch a movie about computers and video games? Sprinkle in some computer animation and how could I not fall in love.

One of the coolest movies when I was a young teenager was Disney’s Tron. What geeky kid didn’t want to watch a movie about computers and video games? Sprinkle in some computer animation and how could I not fall in love.

Needless to say, Tron was the inspiration for more than a few of my programs. Trail Blazer, September’s program of the month, is one of them. An homage to the light cycle segment, the goal is to crash your opponent first. But beware. All walls are deadly, including your own.

A different kind of game play.

Using the ZX81 arrow keys to move, position your trail in a way to trap your opponent. Be careful that your opponent does’t run you into his jet walls though. (See what I did there?) Unlike my other games, the black trail’s movement isn’t just sporadic randomness.

To start, I reduced the chance of your opponent turning. This creates longer walls that you could skim down—just like in the movie. Due to the reduced chance of a turn, it can be more surprising when it does.

My next change was ensuring your opponent won’t just turn into your wall. Due to the slow response of ZX81 games, I generally didn’t bother to do this, but I did in this case. It could be smarter, but these changes make Trail Blazer unique next to my other trail games.

This game sure looks familiar.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that Trail Blazer looks familiar. Written in 1984, the walls and trails look like 1983’s Electon, featured last month. Two more trail games I’ve shared, both from 1985, are Spiders £ Flies and Bonkers. Having similar looks, all three are distinct games.

None of the three use the same code. Although elements are similar, I took different approaches for each. I experimented with different styles, creating unique approaches to similar play styles.

Note that none of my games were snake programs as they didn’t keep track of the tail. Don’t take that to mean that it isn’t possible. Ether I didn’t think about it, or I thought it would be too slow.

Thinking about it now, I’m pretty sure I could create one. And, I might just do that.

Gee that code looks pretty.

Well, at least it starts out looking pretty. With comments and branches, the beginning of Trail Blazer looks like a modern program. Many of my programs today start as pseudo code, which is what this looks like. Yet, back in 1984 it was pretty rare for me.

The rest of the code doesn’t look so nice. Those branches at the start jump to uncommented functions that don’t break nicely. I generally created functions that had line numbers ending in 00s. Not this time.

Following the code can be difficult as well, especially the computer's movement starting at 400. You have to track GOSUB and GOTO jumps that lead to RETURN lines that may not make sense at first. It works, but could flow better.

I see a pattern here.

Speaking of the computer’s movement, you’ll find that the computer leads to the left. Like the player, I use the arrow keys, 5–8, to move your opponent. It makes the code easier to read. Yet, this line causes a bias.

430 FOR A=5 TO 8

You see, if what’s in front of it isn’t a blank, that loop is used to check if it can move elsewhere. Since 5 is left, it is the first place it will turn. Next is down, followed by up, and then right last. If not for the random turn on line 401, the bike’s movement is fairly predictable.

If I were to change anything, fixing this bias would be it. There are couple of methods to use, including random checks like I did in Electon. Yet, it isn’t a fatal flaw. Although, it does tend to fill up the left side of the screen.

Creating straight lines is fun.

One unique thing with Trail Blazer is that both you and the player keep moving each turn. I use the variables D1 and D2 to track direction. The problem comes in how I change them.

As noted earlier, the computer uses the number above the arrow. Lines 410 and 450 set D2, which is a good thing since it isn’t set before that line. The routine at 610 then sets the bike’s new location.

610 LET X2=X2-(D2=7)+(D2=6 )

620 LET Y2=Y2-(D2=5)+(D2=8 )

630 RETURN

The player, on the other hand, has to hit a key. The variable L$ holds the value of the player’s turns which is then used to move your trail.

330 LET L$=INKEY$

340 IF L$="" THEN LET L$=STR$ D

1

350 LET X1=X1-(L$="7")+(L$="6")

360 LET Y1=Y1-(L$="5")+(L$="8")

370 LET S=S+1

380 LET D1=CODE L$-28

390 RETURN

Lines 350 and 360 look familiar, but there is a problem. If you don’t press a key, line 340 will set L$ to your last direction. But, since D1 is a number, starting out 6 which is down, I have to convert it to a string.

But there is a problem. The STR$ in line 340 is very slow. You’ll find that if you let the computer move you, the game slows down. Hold down a key, and it goes faster. This can be helpful at times, but wasn’t intended.

A better way to handle this would have been to store your key in a string variable, say D$. This would turn lines 340 and 380 into the code below.

340 IF L$="" THEN LET L$=D$

380 LET D1=L$

This speeds up the program—yes, I tried it, as well as simplifying the code. I’m sure I could probably tighten it up even more, but I’m not sure it would make it any faster.

This is it. Come on. Gold-3 to Gold-2 and 1. I'm getting out of here right now, and you guys are invited.

– Kevin Flynn

I could write all day about all the things I could do better, but it doesn’t matter. Programming is a journey and at some point you just have to let the code go. A few minor tweaks aside, Trail Blazer is a decent game.

That said, it could be a fun game to convert to MCODER or, even better, a Javascript game. For now, I’ll leave that challenge to you.